Design of a Racer

Vibrations from the engine run up your spine, into the brain, endorphins overflowing into your hands as the throttle twists and brakes are applied in harmony, on the thin line of unwavering control & emanate disaster, exiting the corner reaching speeds of 140mph, inches from the concrete barrier that separates the racing surface from a stadium filled with boisterous fans, surrounded by 17 other racers experiencing similar sensations.

My earliest memories are from behind the handlebars of a motorcycle. It was clear that these two wheeled machines were intrinsically connected to my DNA, but what wasn’t apparent is how these visceral experiences of riding a motorcycle would shape the rest of my life.

But what does this have to do with design?

Learning to ride a motorcycle coincided with my introduction to the garage and all the powerful form making tools, machinery, and opportunity that it contained. Though I did not know it at the time, it is in this garage with my father that would be my first exposure to design – as the designer and as the user. See, one cannot (or should not) ride a motorcycle without having the fortune of breaking and fixing it, tearing down and rebuilding it, and making your motorcycle your own.

A lifestyle filled with motorcycles and all that went with them was passed down to me by my father, who rode most of his life and had raced professionally for 17 years. It was at the track where my father felt at home, would meet my mother, and learned what it meant to be his best and push his limits. It was here where my family would spend 30+ weekends a year together.

By the age of 16 we had decided it was time to get serious about racing. At the age of 19, I earned my Profession American Flat Track License and began traveling the nation, chasing my dreams, and getting paid to go fast.

Concurrently, at 19 I also began my journey into architecture. Here, the garage was referred to as the “studio”, but it held many of the same form making characteristics as my father’s garage.

Through my racing career and my education, I became enamored with the idea of making a meaningful connection between the two, but I never understood exactly what that meant and to be honest, I still do not. What meaningful connection can be made between designing the built environment (Architecture) and the visceral experience of racing a motorcycle? Perhaps, the connection wasn’t a physical one as I had been searching for.

As a racer you can look at the track and see the racing line that is obvious, it’s fast, it’s consistent, and if you ride your best and make one less mistake than your competitor, you might just win. But the best racers look beyond. They look for more. More: traction, moisture, stability, they look for the line that their competitors haven’t considered. The unique perspective to do things differently, to not follow in the tracks of others, but to find the fastest way around the racetrack. I can remember my dad saying to me “Everyone puts on their boots the same way. Just because no one else has tried it, that doesn’t mean it won’t be the fastest.” My dad was exceptionally good at making me believe I was just as capable as the best in the world. And sometimes, all you need to do is believe it.

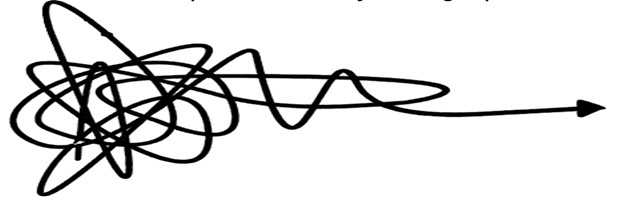

On most racing surfaces, the obvious line is most used, makes sense. On a dirt racing surface, repetitive use by 18 riders over hundreds of laps causes that line to evolve throughout the day.

The surface becomes harder, dryer, and rubber from the tire is bonded to the dirt forming a dark groove. Depending on the weather conditions, time of day, the type of soil, the track preparations, etcetera, the groove could be the fastest way around the track, or it could not.

The latter are the days when I thrived at the track. After the sun goes down, the moisture comes up. The moisture unveils traction on the racing surface that previously did not exist, but only to those who dare. Typically, the racing grove is near the ‘bottom’ of the track, and can be the shortest, fastest, and safest position on the track. When the conditions aligned, it is above the grove where you found most traction and a competitive advantage, but with a much higher risk. Here you can carry more speed and loose less momentum. It is in these moments, where applying the known to the unknown can send you to the front of the pack.

In essence, that is just what great design does. Great design doesn’t follow. Great design takes something known, something proven, and uses it for something unknown, in a new light, in a new way, creating something else, unique. This exploration makes a designer vulnerable… for failure but also for success! Just as a racer can shoot to the front of the pack or fall far behind. But it is experimentation that is key to success, by using the knowledge you’ve gained, learned, experienced, and applying it to the unknown to advance your position.

To be a successful racer you must train your body and mind to react to things before they happen. Intention must be instinctive. Whether it be a condition of the climate, the racing surfaces, your competitors… You must anticipate what your body needs to do, to inform the motorcycle how to respond to what is to come. In other words, you must act with intention. Without this mindset, the motorcycle becomes unpredictable. An example of this would be drifting the motorcycle before it loses traction allowing you to maintain control.

Another technique that requires intention is drafting. Though we are not talking about the kind of architectural nature. Drafting is an aerodynamic racing technique where two motorcycles align in a close group, reducing the overall effect of drag due to exploiting the lead motorcycles slipstream. To draft a motorcycle, you must align behind your competitor, remove your hand from the handlebar which drops your shoulder and pulls your body further from wind resistance. Because of the reduced wind resistance, you are sling shot past your competitor.

Intent and design go hand in hand. A designer is asked to intentionally research, analyze, think, ideate, and inevitably create. When designing a chair, one must intend for it to be comfortable for it to be. One must understand the structural properties of the materials for it to be self-supporting. Intent at all levels of design must be applied for a design to reach its maximum potential.

“To voluntarily restrict one channel of information is foolish for a racer; to allow information to flow unfettered is divine.”

Countless things are happening simultaneously when a racer is on the saddle of his steed. Moving at high speeds doesn’t allow you to focus on anyone thing for more than a moment, yet all five senses are engaged. You see what’s ahead, passively preparing your body to make its next move. You hear your engine, and your competitors around you. You smell racing fuel, your tire burning away. You taste the dryness in your mouth and likely a little dirt and rubber too.

With all that is happening as you hurl yourself around a racetrack at 100 plus miles per hour, it is important not to focus too hard on anything. This allows the information to flow unfettered, and leaving your mind to process anomalies as they arise.

A designer must also react to all that surrounds the design problem. They must react to the client, the end user, our planet, comfort, aesthetics, building code, site constraints, orientation to the sun, wind, the community, the list goes on……. To restrict any of these streams of information has the potential to lessen the design outcome.

When you are lying in pieces on your floor, this is when you have the most power. “Without any idea how to move forward, your expectations of the future become meaningless. Your stories about the past are meaningless. You are in flux, you are changing, you are flowing in a new way, and this is a powerful opportunity to become new again: to choose how you want to put yourself back together.”

One must get comfortable with being, never not broken. By accepting we will always encounter roadblocks, dilemmas & setbacks, it changes the narrative to one of rebuilding oneself, full of promise, and most of all, what you make of it.

No design will be perfect, very few clients will have 100% satisfaction, most ideas won’t make it past the drawing boards, but by having this mentality, it fuels the creative spirit to rebuild, break it down, and rebuild it again.

The iterative design process is unrelenting and beautiful. An idea can be mulled over for hours, for days, only to be scrapped. But the journey doesn’t end there, because within this process, many other ideas, methods, routes have sprouted, and each of those can be taken down a similar process. As a designer and a racer, you must embrace the mystery.

What meaningful connection can be made between designing the built environment (Architecture) and the visceral experience of racing a motorcycle? Perhaps, the connection isn’t a physical one as I had been searching for but rather, the tendency as humans to create dualities among the themes in their

lives.